THE ARCHITECTURE OF WALKING IN BETWEEN

The architecture of bungalow courts and the art of living in between

“Chaos is a friend of mine.”

— Bob Dylan

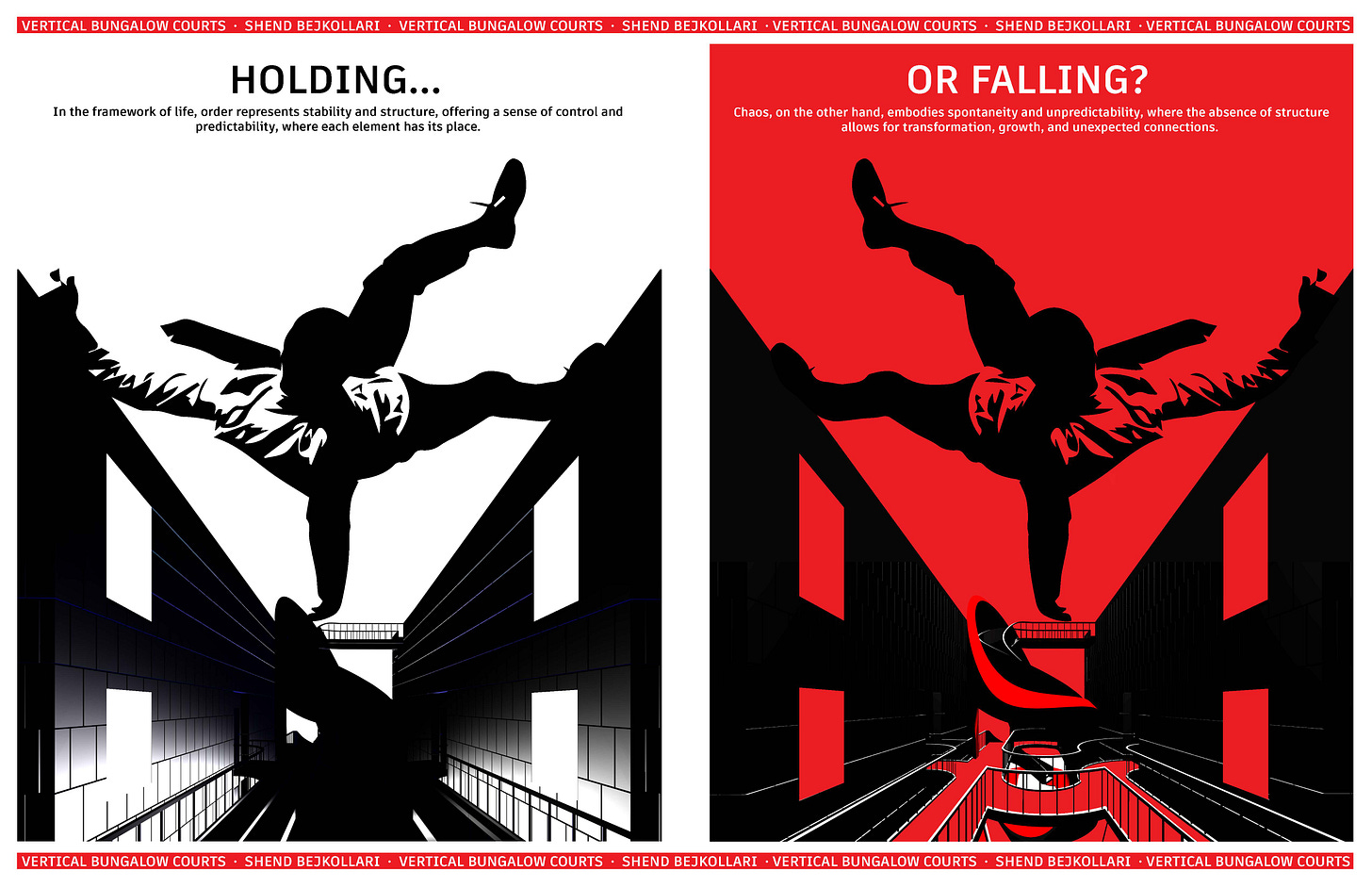

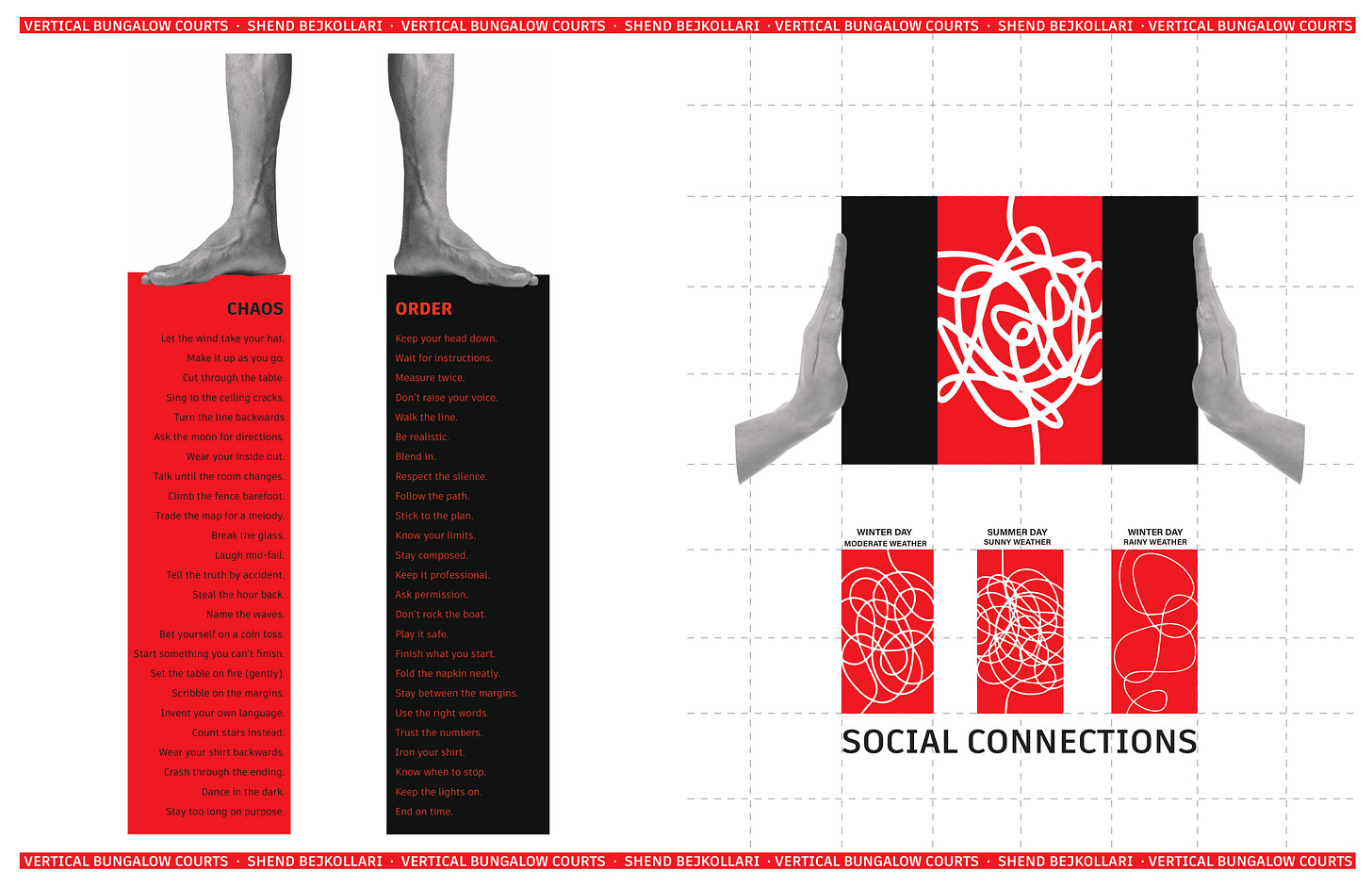

In the grand spectacle of existence, life presents itself as a perpetual dance between chaos and order. This interplay between opposites has captivated humanity’s interest for thousands of years and has expressed itself through countless songs, paintings, books, plays, conversations, and buildings, prompting reflections on the structures — both literal and metaphorical — that frame our experiences.

This project emerges from that very tension. It explores how architecture can embody both stability and spontaneity, permanence and change. By reinterpreting a historic housing typology through a contemporary lens, the work asks:

How do we create places that allow for both individual sanctuary and unpredictable social encounter? How can typology act as a framework, but leave room for the unexpected?

From ancient Greek philosophy’s notion of cosmos emerging from chaos to quantum physics’ delicate balance between probability and precision, this tension remains central to how we understand the world and our own lives…but first things first, The Beatles.

I. The Symphonic Duality

Consider their 1967 opus, A Day in the Life — a masterclass in dualism. The song merges two distinct sonic worlds, two ideologies, two interpretations — “forced” to stay together — yet beautifully completing each other. Lennon’s melancholic, dreamlike verses — haunted by the then-recent death of Tara Browne, which he read about in the newspaper (an inspiration “technique” which he used not only throughout this song but generally all throughout his career) — emerge from a space of reflection and unease. McCartney on the other hand, pushes the song forward with his characteristic bright, “good day sunshine,” everything-is-going-to-be-alright kind of way, reminiscing about his early school days in Liverpool, running down the stairs, brushing his hair, leaving the house and trying to catch the bus. It’s optimism crashing into tragedy, the mundane colliding with the surreal.

John, very simply, summarized the entire song as, “A good piece of work between Paul and me. I had the ‘I read the news today’ bit, and it turned Paul on, because now and then we really turn each other on with a bit of song, and he just said ‘Yeah’ — bang-bang, like that.”

That “bang-bang” is the alchemy of opposition — the spontaneous combustion of dual perspectives. Just like that, they captured the contrasting duality of our lives: between optimism and pessimism, life and death, beginning and end, the mundane and the surreal, the structured and the spontaneous — order and chaos.

And all of it stitched together by a gigantic, seemingly random (though carefully crafted to perfection by George Martin, in itself a beautiful idea of chaos and order…chaotic on the outside, but orderly crafted with precision to make it feel chaotic) ever-increasing crescendo of orchestral chaos. Funnily enough, it was played by a 40-piece orchestra — half of what McCartney originally wanted — but the recording was overdubbed multiple times, filling a separate four-track machine, a technique they often used to transcend technical limitations. What sounds like randomness is actually a meticulously orchestrated explosion, capturing the sound of a world spiraling upward — or inward — depending on how you listen.

In short, Lennon described this 24-bar middle section as “something absolutely like the end of the world.”

The melodic infinity of this dance was portrayed as a never-ending E piano chord, playing endlessly after the reprise of the orchestral cacophony, a fitting “end” to a masterpiece. It lingers, unresolved yet conclusive, fading out like a dying star. Five minutes and thirty-five seconds was enough for The Beatles to capture this theme perfectly in their art form — but this has certainly been attempted by countless artists throughout the ages. The Beatles just offer another example of it — though admittedly, a very good one.

The Beatles captured in one song what artists, philosophers, and mystics have tried to articulate for centuries: the inseparability of opposites. The duality of chaos and order is not a flaw in the human experience — it is the very essence of it.

II. The Bungalow Court Typology

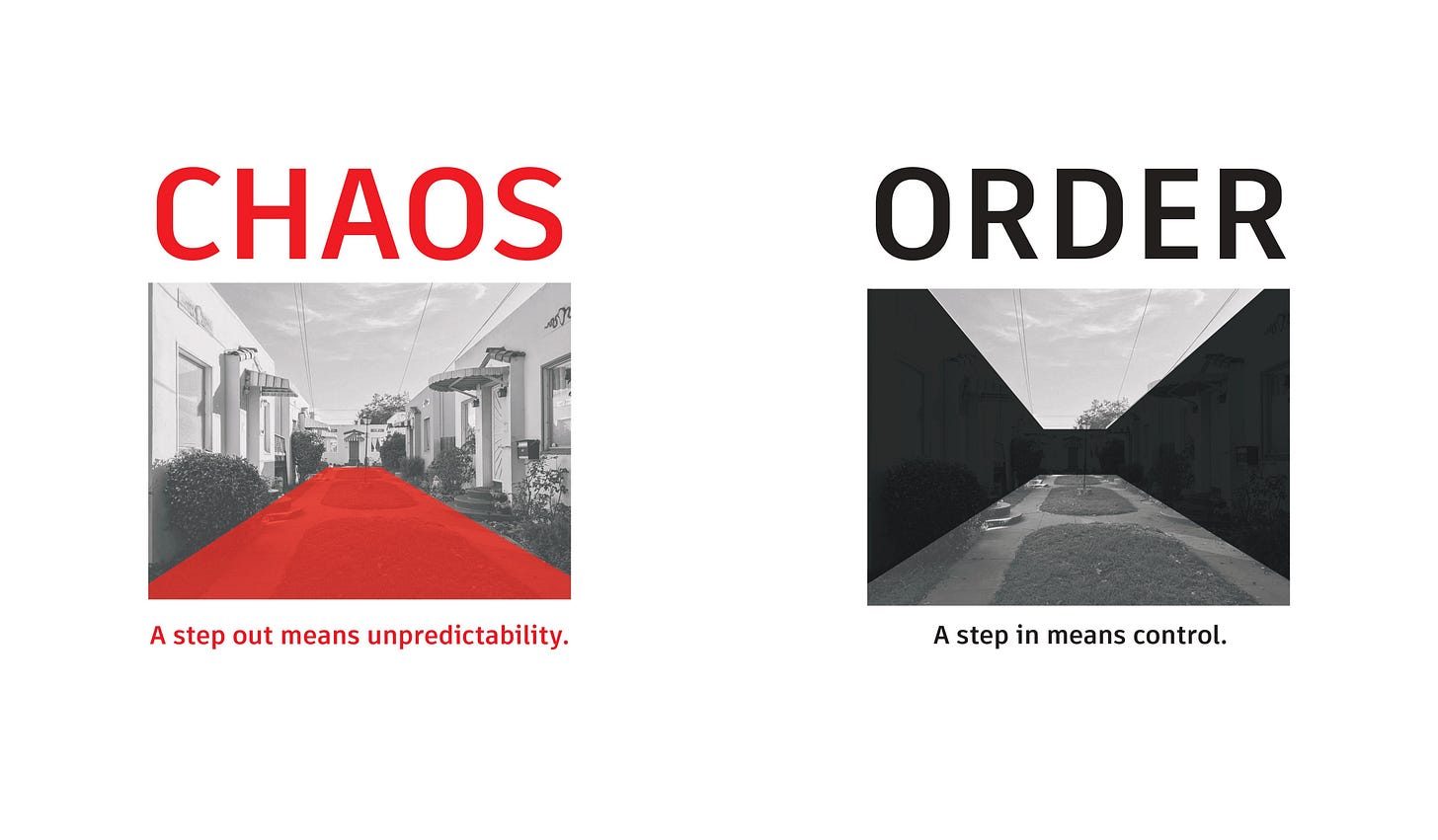

Architecture, too, grapples with this duality. The bungalow court typology, prevalent in early 20th-century Los Angeles, presents a harmonious blend of private and communal spaces, with a clear, almost intuitive understanding of the human need to constantly move between order and chaos. On one hand, you have the individual residences — lined up, facing each other, identical from the outside. Yet inside, each becomes a sanctuary for the family that inhabits it. Here, the most basic building block of our society — the family unit — takes center stage.

Their repetitive nature, along with the restrained, almost ritualized way of living they promote, represents order. From one bungalow court to another, the concept rarely changes. The architectural styles may vary — Spanish Colonial Revival, Craftsman, Tudor — but the spatial logic stays the same: multiple individual residences mirroring one another, creating a safe, controlled space set apart from the larger, often chaotic world.

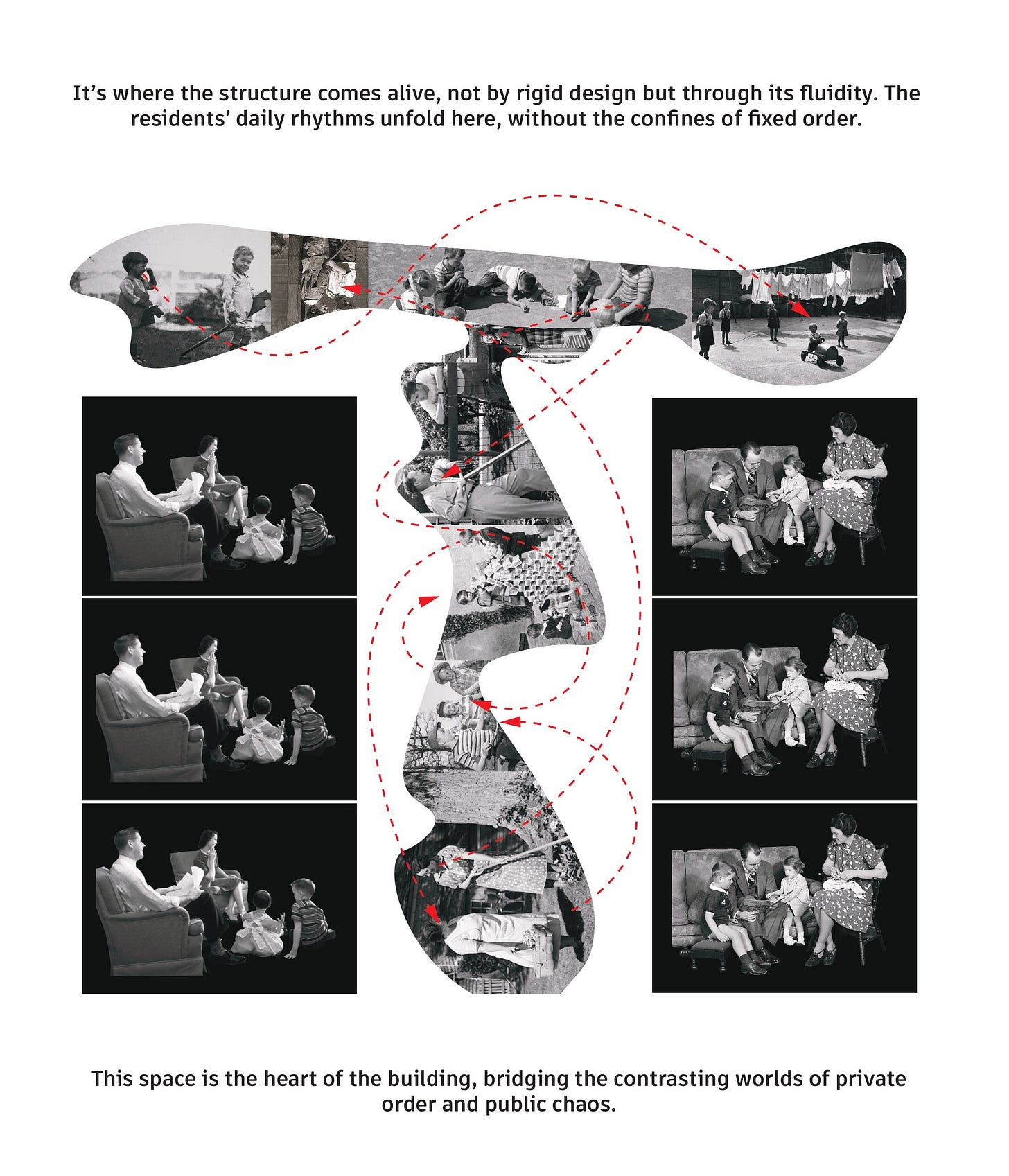

On the other hand, the space in the middle — the glue that holds these homes together — is something altogether different. It’s a social zone that varies wildly from court to court. It may change in size, in ideology — whether it prioritizes people or cars — in landscaping, architectural detailing, and in the number of ways one can traverse it. This space represents chaos, or at least, unpredictability. You step out of your private, climate-controlled bubble — where you are king, president, or emperor depending on your mood — and suddenly, you are vulnerable to the unknown.

Not unknown in a physical sense, because the space is familiar. But socially, it is in constant flux. Children play, neighbors chat, people come and go. The choreography of everyday life unfolds here, without a script. Nothing is hidden. The space demands participation. The connections made here — fleeting or long-lasting — are spontaneous, unscripted, and often transformative. Movement in this space is governed not by architecture alone, but by chance, by weather, by mood, by time.

Unlike the sanctuaries our homes provide, this middle space is open to the elements. It doesn’t shy away from chaos — in fact, it embraces it. It sits proudly between order, confronting the world without flinching. The contrast this typology creates — placing a social zone between two flanks of mirrored order — becomes a metaphor for our lives, our times, and our constant negotiation between comfort and confrontation. You almost wonder if Lennon and McCartney once stayed in a bungalow court before writing A Day in the Life.

This contrast — between rigid order and shifting chaos — mirrors our daily experience. It is the same tension we find in Lennon and McCartney, in Greek tragedy, in Zen koans, in a Dylan line or Shakespeare play. And here it is, expressed not in a monumental cathedral or a giant statue representing a historic battle, but in humble domestic architecture. A few bungalows facing each other. A path. A tree. A bench.

The bungalow court tells us something profound: that our lives, like our spaces, are shaped in the in-between.

III. Reimagining the Bungalow Court

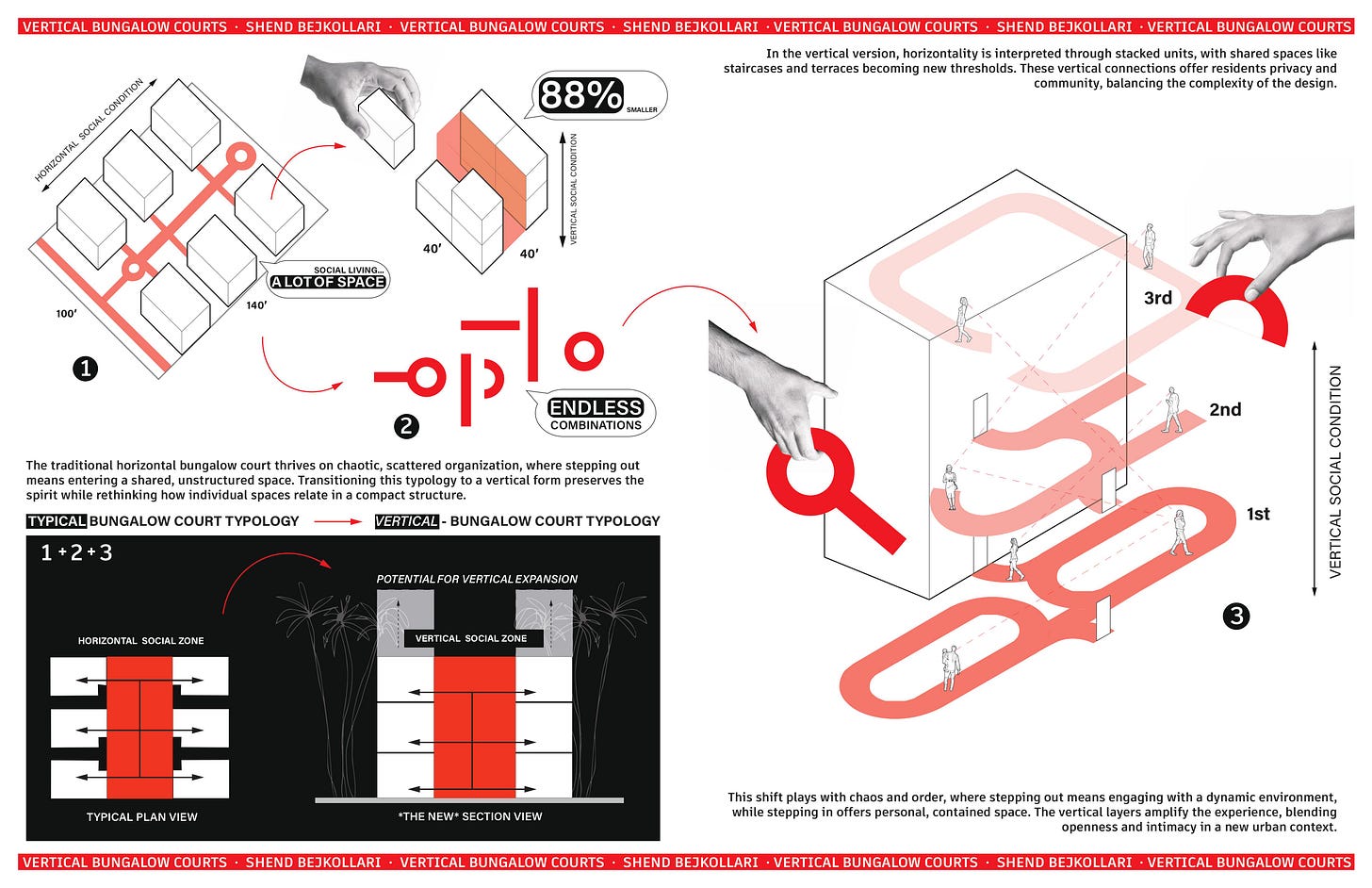

This project began as an entry to the “Small Lots, Big Impact” competition — which posed a challenge faced by many rapidly densifying cities like Los Angeles: how can we house more people in smaller lots without sacrificing individuality or the human need for social connection? The original question set up a tension — a negotiation between chaos and order — that seemed to mirror the everyday contradictions of urban life. That tension became the project’s anchor point, and while it began as a competition proposal, and certainly a lot of the competition’s requirements are evident in the design of the building- things like height, width, number of units, zoning regulations — it quickly transformed into something deeper and more expansive. The competition’s framework and language remained, though the idea of the project kept evolving.

The bungalow court offered a compelling starting point. It provided a model where individuality and community coexisted within a shared physical language. But in today’s reality — marked by land scarcity, rising housing costs, zoning logistics and the vertical logic of cities preventing this typology from being built again in the same form — simply repeating that horizontal form no longer suffices.

This project asks: How can we translate the principles of the bungalow court into a contemporary vertical framework?

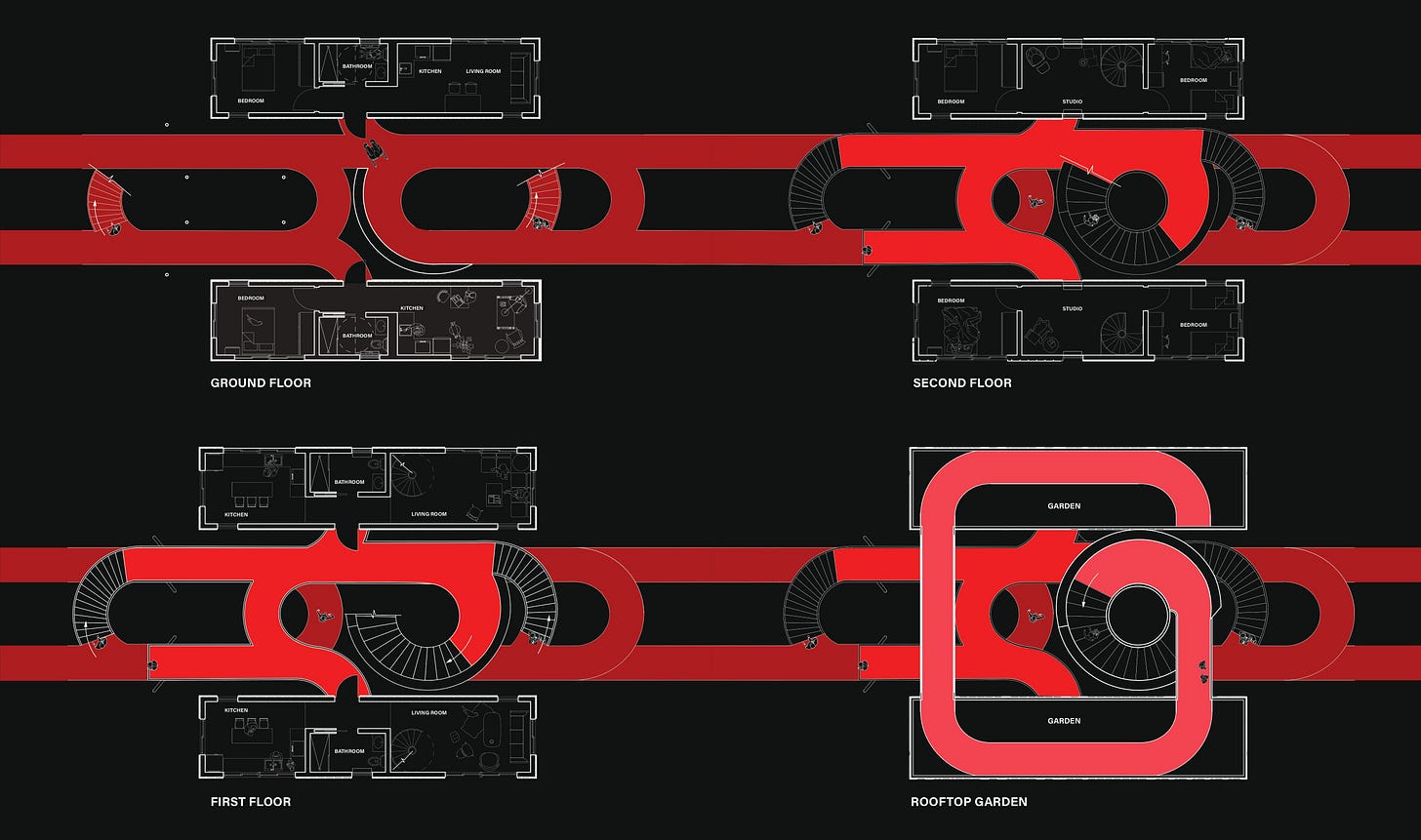

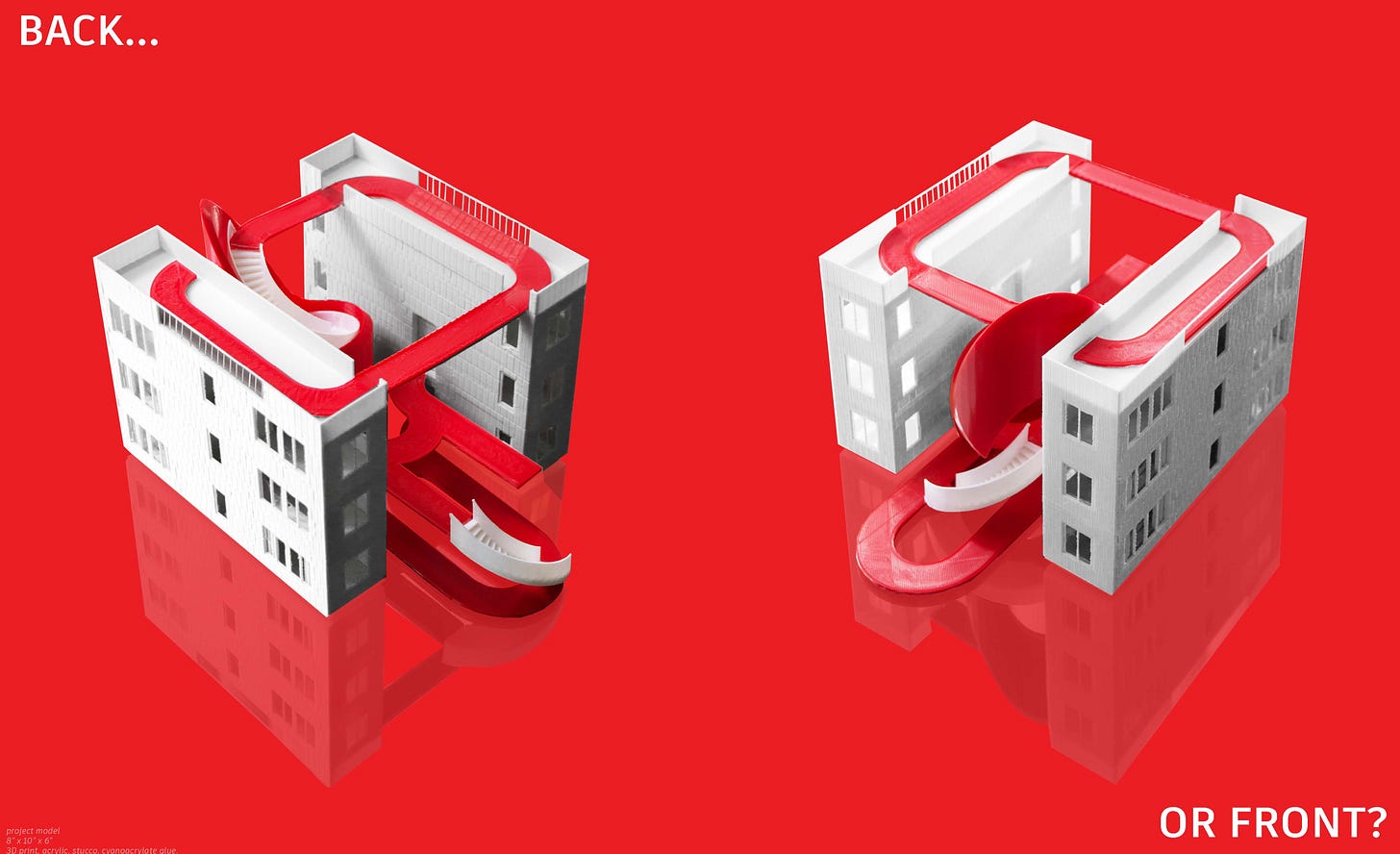

The answer began with reimagining the bungalow court through the lens of dimensional transformation. Much like the inhabitants of Edwin A. Abbott’s Flatland, who were constrained by two-dimensional thinking, traditional bungalow courts occupy a horizontal plane. But what happens if we flip that social space vertically? In this project, the social zone is extruded upward, layered floor by floor between two vertical blocks of residences. By adding verticality, we give depth to the typology, creating a new architectural language that brings with it fresh opportunities for interaction, ritual, and complexity.

In this version, the units are stacked on either side of a central void, creating a sense of communal individuality, where each unit’s identity is defined not in isolation, but through its relationship to the collective whole. This void becomes the project’s spatial and symbolic heart: a vertical social zone that threads through every floor. It is where movement happens, where people cross paths, where architecture becomes alive and unpredictable. The homes themselves may be formally ordered, their elevations aligned, but what unfolds between them is anything but rigid. Life — messy, spontaneous, emotional — takes shape in this shared middle.

Unlike typical multi-family housing, where individuality is confined behind walls and community often feels manufactured, this typology reorients the idea of identity. Here, the individuality lies not only in each unit, but in the collective behavior of its residents. The social zone, if the typology is replicated elsewhere, allows for architectural flexibility — it can be tailored, adjusted, designed, reshaped, redesigned depending on who lives there and what they need. In one iteration, it might serve as a series of gardens or informal gathering spots; in another, it might become a playground, a gallery, or a vertical park. This, ideally, gives “power” not only to the architect to design, but also to the residents to propose their needs and wants. Even if the scenario that the building is replicated identically elsewhere, the center — the space of chaos — is always different. Because people are different. Routines are different. What binds them together is not a fixed formula, but an adaptable scaffolding for life.

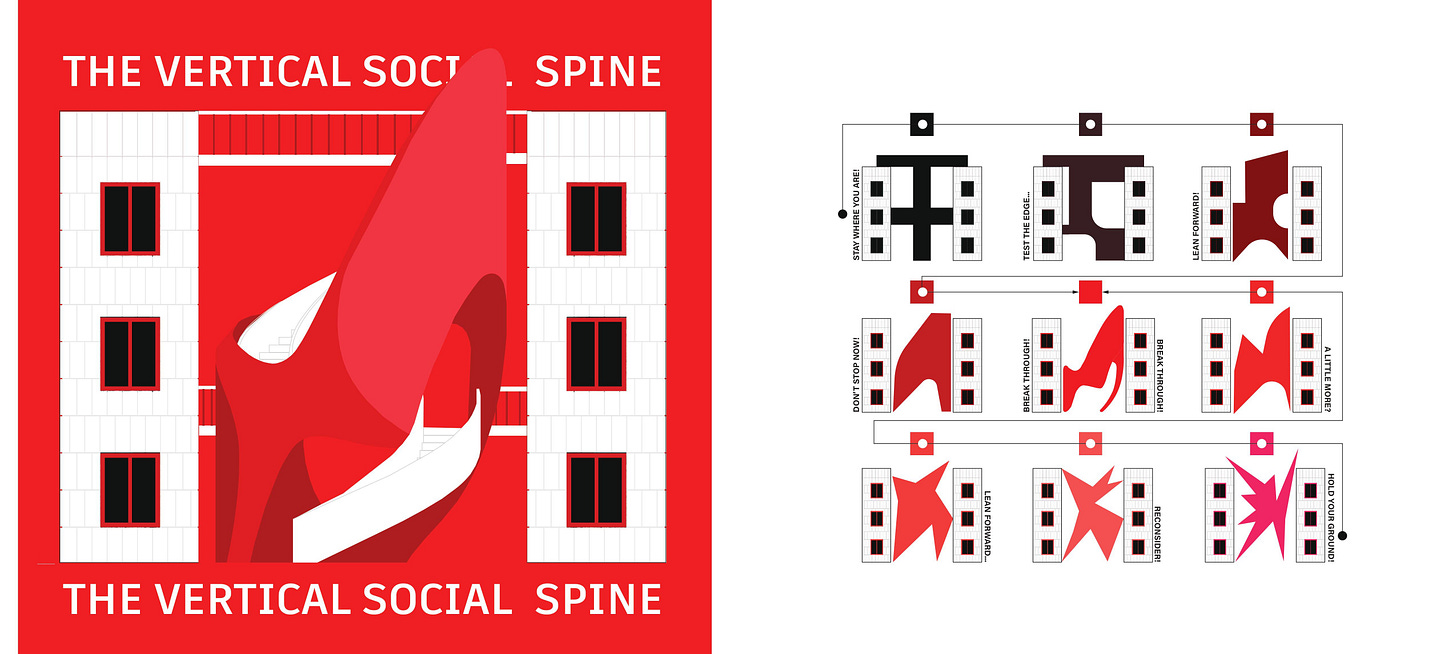

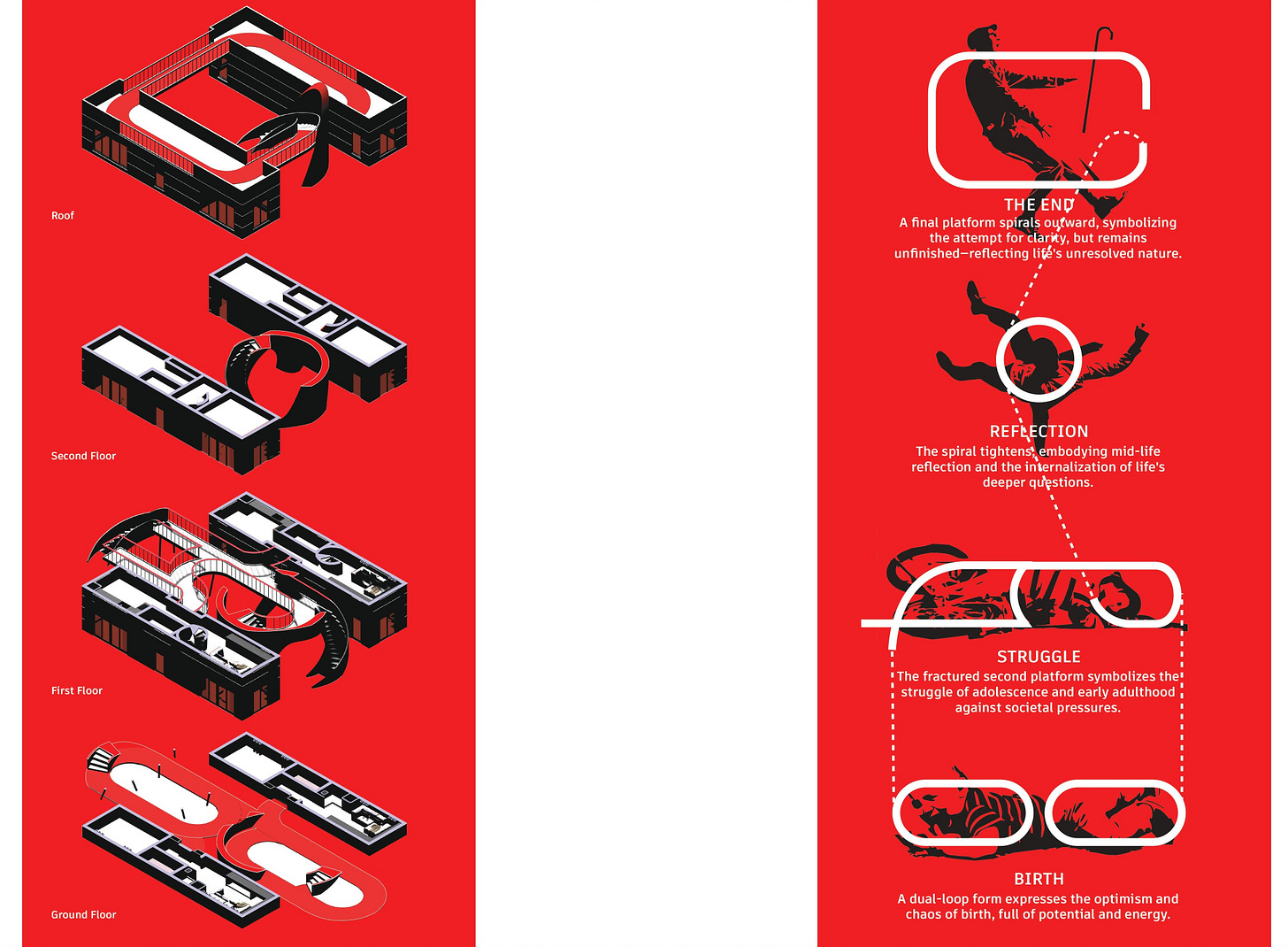

This idea is crystallized in the central sculptural element — a twisting vertical structure that houses circulation, pauses, and moments of reflection. A stair climbs through it like a snake wrapping around a tree, revealing and concealing paths as it weaves upward. The stair is not just a connector, but a metaphorical journey through life’s stages, embodied in the platforms and architectural gestures encountered along the way.

On the first level, a dual-loop form captures the intensity and optimism of birth: chaotic, yet full of optimism and endless possibility. The second platform, representing adolescence and early adulthood, fractures and twists the previous loop — symbolizing the constant battle to define oneself amidst the expectations and constraints of family, society, and biology. The third stage is one of introspection. Here, the form tightens, pulling upward in a more contained spiral, creating the form of a circle moving upward. It reflects the questions that surface in the later stages of someone’s life, a mid-life reflection period with questions such as: Was it worth it? What can still be changed? The architecture compresses, mirroring the internalization of those thoughts.

At the top, the journey culminates in a long, final platform that spirals out and around both towers — an attempt to close the loop, to reach clarity — but it falls just short. The platform loop curves inward, with its end looking back on everything that came before. It becomes a space of final reflection, representing the inevitability of an ending that remains incomplete. Life, like architecture, always holds unresolved tensions.

In this typology, the social void — this core of orderly chaos — becomes both the physical and emotional center of the building. And it is never the same twice. A different architect could design it elsewhere and it would manifest differently. That’s the point. A different group of people could live within it, and it would evolve in a new direction. That’s the point.

Ultimately, this project is not just a housing typology. It is an architectural proposal for living with contradiction, that has been and should continue to be used: balancing repetition and uniqueness, structure and openness, solitude and collectivity. It proposes that even in a world where space is limited, simplicity must be evident and constraints are many, architecture can still honor the full complexity of human life — not by resisting chaos or drowning in order, but by embracing the battle between the two of them.

FOR MORE INFORMATION ABOUT THIS PROJECT VISIT: